Prepared by: Vinchel Budihardjo

& Truong D.Vu

Use of

The

usefulness of financial statement projections for corporate financial

management is undisputed. Such projections, called pro forma financial statements, are the bread and butter of much

corporate financial analysis. Pro forma financial statements look at the links

between the balance sheets and income statements and more importantly the flow

of funds in the future. A pro forma income statement is similar to a historical

income statement, except it projects the future rather than tracks the past. It

the projection predicts a downturn in profitability, you can make operational

changes such as increasing prices or decreasing costs before these projections

become reality. A company’s future profitability, borrowing and many other

quantities are all highly uncertain quantities. It seems natural to run a

simulation to obtain a range of values on future profitability and borrowing.

Simulation is related to both scenario and sensitivity analysis. It ties

together sensitivities and input variable probability distributions. We can

play the usual “what-if” games of simulation models, and we can ask what

strains on the firm may be caused by changes in certain variables such as sales

and expenses. The purpose of this exercise is to illustrate the use of Monte Carlo Simulation to form the

basis for valuation and credit analysis. First of all, we need to get the

historical financial statements data for Home Depot and then we create a

simulation.

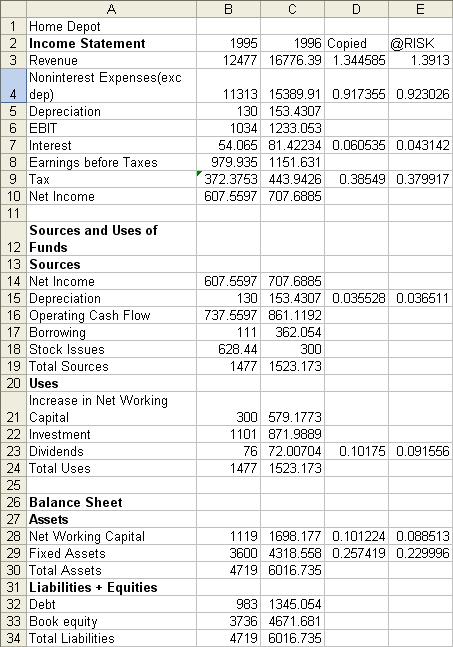

Relevant Data

Figure 1

below shows the relevant data for Home Depot in 1995. All numbers are in

millions of dollars. Note that Sources = Uses and Assets = Liabilities +

Equities. Given the actual financial statements for Home Depot, we can forecast

their financial statement for the next year (1996). Next year revenue (t+1) is

simply the value of t (current year) multiplied by a constant value shown in

column D. This is the trick in linking year t with the next year (t+1). To see

the key relationships, click here to get the

spreadsheet. Since, the spreadsheet is an @Risk spreadsheet, you also need to

get .rsk file. After running the simulation, both Excel (XLS) and @Risk (RSK)

files need to be saved separately. If the associated .rsk file is not saved,

then reopening an Excel file necessitates rerunning the simulation to obtain

the results.

Figure 1

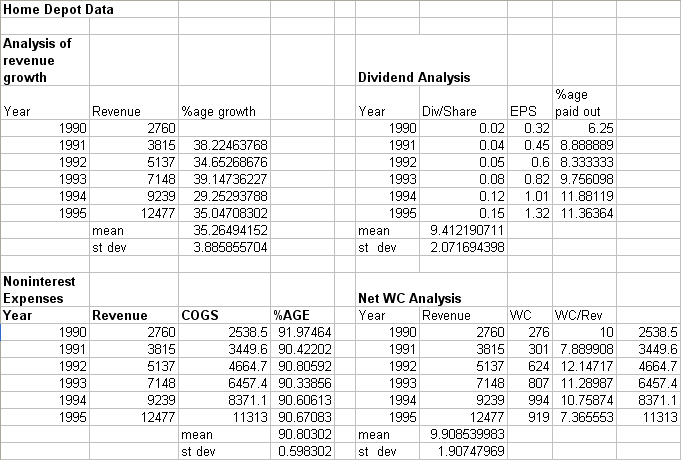

The Dynamics of the Model

In a simulation analysis, the computer begins by

picking at random a value for each of the uncertain variables (Revenue Growth, percentage of Non-interest expenses to

Revenue, Interest rate on Long-Term debt, Tax rate, Depreciation on

Fixed-Assets, Dividend payout rate, Net WC and Fixed Assets) based on

its specified probability distribution. We assign the following names to these

variables: a1-a8.

Figure 2

The mean or average value is used as a measure of

expected value and the standard deviation (or coefficient of variation) is used

as a measure of risk. The assumption here is that each of the eight items can

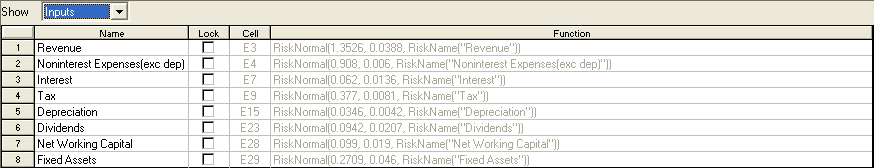

be represented by a continuous random distribution. We make them =RISKNormal functions to model the fact

that each constant may differ in different years. This drives the randomness of

the model. As an example consider a1 (Revenue Growth). This

parameter measure the year to year growth in revenue. For 1991-1995, we found

the average growth in revenue to be 35.26% and the standard deviation to be

3.89%. To model the simulation, we use the formula RiskNormal (1.3526, 0.0388).

The formula for a2 = RiskNormal (0.0991, 0.0191).

Here’s the list of inputs with the formulas assigned:

If you look at the Financial Statement data, you

will notice that net income influences borrowing, borrowing influences debt,

debt influences interest, and interest influences income. In Excel, this is

referred to as circular reference. There is a way of resolving the circular

reference problem. Simply go to “Tools”, then choose “Options” “Calculation”

“Automatic” and check “Iterations” and put in 1000 for maximum iterations. You

will see that Assets = Liabilities + Equities and Uses = Sources.

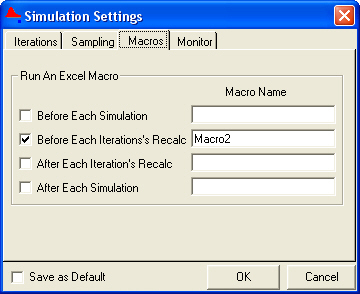

Before running the simulation, we will create a

macro that will paste the constant value (as numbers, not formulas) from the

simulation (column E) to column D. Then it will feed into column C and it will

resolve the circularities. The macro name used is Macro2. Under @Risk

simulation setting, we ask @Risk to run Macro2 before each iteration of a

simulation. The sequence of events would be:

- Run

Macro2

- Compute

@Risk functions and calculate output cells

- Run

Macro2, etc

This ensures that before each time the value of an

output cell is tabulated, new values of a1-a8 will be

generated.

We’re now ready to run the simulation. The only

output we are trying to measure is the Net

Income. After 1000 iterations, @Risk produces the following results:

|

Summary Statistics |

|||

|

Statistic |

Value |

%tile |

Value |

|

Minimum |

505.4887695 |

5% |

674.0304565 |

|

Maximum |

1102.032837 |

10% |

705.9438477 |

|

Mean |

811.5698513 |

15% |

725.0234375 |

|

Std Dev |

85.46608282 |

20% |

743.0560913 |

|

Variance |

7304.451313 |

25% |

755.5171509 |

|

Skewness |

0.039828427 |

30% |

766.8305664 |

|

Kurtosis |

3.216118724 |

35% |

779.039856 |

|

Median |

810.1477051 |

40% |

790.0019531 |

|

Mode |

818.5773621 |

45% |

801.8696289 |

|

Left X |

674.0304565 |

50% |

810.1477051 |

|

Left P |

5% |

55% |

819.0309448 |

|

Right X |

952.2886963 |

60% |

828.7329102 |

|

Right P |

95% |

65% |

840.2873535 |

|

Diff X |

278.2582397 |

70% |

848.4483643 |

|

Diff P |

90% |

75% |

865.7454224 |

|

#Errors |

0 |

80% |

882.7453613 |

|

Filter Min |

|

85% |

900.5479736 |

|

Filter Max |

|

90% |

923.5115967 |

|

#Filtered |

0 |

95% |

952.2886963 |

A picture is worth a thousand words and the summary

statistics above shows the probability distribution of the outcome. We see that

on average, we expect Home Depot’s 1996 Net Income to be 811 million. They

actually made 733 million (according to the actual data), which was in between

the 15th and 20th percentile of what we expected.

@Risk is such a powerful tool in that it gives you

countless reporting and graphing options. To see the complete results, click here.

Conclusion

We can use this simulation technique to forecast as many years ahead as we like. This does not mean it goes with the expectation that past revenue growth assumptions hold. A company could have its business cycle and as such is on S-shaped curve of growth that most companies follow. Also, the industry is expected to become more competitive. This could affect some of the variables we used such as margin (as factored into a2). This model gives you flexibility to build in (with If statements) future assumptions about the industry and the firm behavior (for example: stock issuing policy). In the example above, the revenue growth follows a random normal variable. We could have instead used the other function that takes some of the values as equally likely scenarios of future growth. Let’s say, the revenue growth could be one of the following values: 1.3822, 1.2565, 1.3952, or 1.2585. Instead of using the =RISKNormal function, we could input the function: RISKDUniform({1.3822,1.2565,1.3952,1.2585}) as the formula.